D2D: Huawei Deep Dive

This week we take a look at Huawei's ambitions in semis, autos and beyond

Executive Summary

Huawei is probably the most influential technology company in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) today, and one of the most influential globally. It has seen tremendous growth, not just in terms of financial metrics but also in the scope of its capabilities and ambitions. Despite that, it is still poorly understood, especially outside of the PRC. In part, this lack of understanding is the direct result of the company’s decades long history of tightly controlling its image, with no small degree of deliberate obscurity. But it has also come to defy ready analysis. It does not fit the mold of a typical US or European company. Over the past seven years, the company was pushed to the brink by US sanctions but has since emerged as a sprawling enterprise engaged in activities across technology domains. Moreover, while the company is ostensibly privately-owned, in many arenas it can look very much like an arm of PRC State Policy. Many of the large questions looming over the future of the PRC electronics industry may very well end up depending on actions that Huawei takes. In particular, we think it is increasingly likely that Huawei is able to make significant technical advances and break into advanced semiconductor manufacturing, sooner than many would expect.

History

If Huawei had started in Silicon Valley, the life of its founder, Ren Zhongei, would be held up as a paragon of entrepreneurial spirit. He grew up in the hardship of the 1960’s PRC. His official biography tells stories of Ren facing near starvation, fights with Red Guards and walking halfway across the country. In the 1970’s he joined the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) where he served in the engineering corps, spending much of his ten years in the service working on automation systems and electronics. He left the PLA in the early 1980’s and moved to Shenzhen, where he worked for a large corporation which he found ‘stifled by bureaucracy’.

In 1987, he founded Huawei. This was a tumultuous time in the PRC’s economic development, when anyone with any ambition left their safe but stagnant jobs in state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to found companies as the market economy opened up. Huawei began as a reseller of foreign telecom equipment like PBX’s. Faced with too many competitors, Huawei began importing components and assembling them locally, moving up the value chain, and then it never stopped moving up.

Through the 1990’s Huawei steadily increased its design and manufacturing capabilities, spreading across the telecom equipment industry. In the early 2000’s it began selling its products for export, benefitting tremendously from the build out of cellular networks. In the aftermath of Telecom Bubble, many of Huawei’s international competitors ended up in precarious financial shape – Nortel went bankrupt in 2009, Lucent owner of the pioneering Bell Labs and once the leading innovator sold itself to Alcatel which itself was acquired by Nokia. Huawei’s rise was a factor in this, as they often priced their products at deep discounts to the competition. During this time Huawei also expanded the scope of its business entering the mobile handset market and then in 2004 began designing its own semiconductors.

By 2019, Huawei was the leading networking equipment vendor, the largest smartphone vendor, and one of the largest suppliers of semis for phones, networking gear and televisions. Then the sanctions came down. The US government began imposing a growing array of sanctions against the company which limited the company’s ability to sell products in the US and other markets as well as access foreign suppliers. Most painful were rules which largely prohibited US chip companies from selling to China and limited Huawei’s ability to source its own chips from TSMC.

The company entered a dark period, seemingly hemmed in all sides. In 2020 revenue only grew by 4%, after years of double digit growth. Even this was not sustainable as the company went through its stockpile of foreign chips. In 2021, revenue fell 29%. That year, Huawei spun off much of its mobile phone business into a new company called Honor. Many feared that the company would shrink much further.

Instead, something unexpected happened. After several years hunkering in the dark, the company transformed itself, almost like a caterpillar emerging from a cocoon. In 2023 and 2024, Huawei began entering new businesses, expanding far beyond its networking base: autos, wafer fabrication equipment (WFE) for semis, software, autonomous vehicles - the full range of 21st century leading technologies. The company even resurfaced in mobile phones and in 2025 reclaimed the top spot in the PRC smartphone market.

Today, Huawei is much more than a network equipment vendor. It is probably the most important tech company in the PRC, and one of the most important in the world, but it is also misunderstood. Its complexity and reach make it hard to analyze as a ‘normal’ company. Here we offer some of the many ways in which to examine the company to give a sense of what makes it so influential.

Huawei as the Bogeyman

When we talk about Huawei in the US, we always have to first overcome a wall of skepticism bordering on hostility. The company has a very bad reputation in the US centered around a series of narratives.

For many years, the most pervasive of these was the idea that Huawei was a just a cheap copycat of Western equipment. This stemmed from its early days reverse engineering imported systems, but persisted well into the 2010’s. The company has never been directly confronted with these allegations in a court of law, beyond some minor incidents. There is a lot of suspicion about them in this regard, but very little hard evidence. Regardless, this view has consistently overlooked the fact that the company has immense engineering capabilities. This was clear even in its early days. The company has a very serious engineering culture, and is the kind of place where the best engineers in the PRC (and elsewhere) compete to work. Say what you will about its past, it is not lacking in technical expertise. Moreover, this reputation as a copy-cat lost a lot of steam five years ago when it was the first wireless equipment vendor to offer 5G products, six months ahead of competitors Nokia and Ericsson. How could they copy competitors’ products when those competitors did not have anything to copy?

Another important narrative around the company centers on geopolitics. Here the story is murky and very complex. Many in the US government have accused the company for years of being an arm of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). This one is tough to shake. Ren Zhongfei has ties to the PLA, and many employees are recruited straight out of service. Moreover, the company has done itself no favors by obscuring its ownership structure. This opens them to the repeated accusation that many of its longest shareholders are PLA officials. The company maintains it is employee-owned, but dig into that ownership structure and it is clear that there are large ownership blocks whose provenance remains unclear. This is reportedly one reason the company never filed to go public.

That being said, it is one thing to question its ties to the PLA, and quite another to accuse it of being a direct agent of the PLA. A common accusation in the US holds that Huawei gear holds back doors to allow PRC intelligence agencies to tap into Huawei networks. Again, there is no hard evidence proving this. We suspect that all telecom gear has vulnerabilities – accidental and deliberate – which allow intelligence agencies access. As one Huawei employee once told us “Don’t hate the player, hate the game”.

Perhaps the most significant narrative around Huawei is the amount of State support it receives. In 2019, the Wall Street Journal calculated that the PRC had given Huawei $75 billion in support covering direct subsidies, tax breaks, discounted real estate, export support and cheap loans. Huawei publicly posted a strong rebuttal of this, including an audit by a Columbia professor. They maintain that the level of support they get from their government is at the same level that Western companies get from their own governments, in their 2024 financials they pinned government support at just over $800 million . This defense relies on analysis of their reported financial results. We will look at those below, but this only offers a partial defense, as those financials are very brief and likely downplay affiliated entities, of which the company has many. At the very least, Huawei benefits from artificially low interest rates that are a major fixture of the PRC’s economic model. Moreover, we know that the company holds immense influence within the PRC. This is evidenced primarily with their relationship with other companies there.

Huawei as Networking Equipment Vendor

Huawei is the global market leader in wireless network equipment, their core business for twenty years. They overtook incumbents Ericsson and Nokia years ago, dropped share in the early years of the US sanctions but have now recovered their top position.

We have heard Huawei executives describe Huawei’s market strategy as “农村包围城市“ or “Let the countryside surround the cities”. This was a military maxim that Mao Zedong used to describe the Communist strategy. (Huawei officials regularly make use of military slogans like this, which does not help to dissuade anyone about their ties to the military.) In this context, it meant that Huawei first focused on markets not well served by the incumbents. This has meant a focus on South Asia, Central Asia, Africa and Latin America. Huawei was known for offering comprehensive solutions where they would sell nascent mobile operators entire networks from cables to core routers. Then they would fly in a few thousand Huawei engineers to bring the system online in a few months. All of this came with highly favorable financing terms from PRC banks (which does not help dissuade anyone about their level of State support). This strategy had its drawbacks, but was largely successful. Huawei networks often ended up being much less expensive to emerging markets operators, at least at first. Over time, Huawei gradually pushed into developed market networks to varying degrees of success. While the US government has been steadily pressuring foreign operators to replace Huawei gear, the amount of resistance they have received in this effort speaks to the lasting value of Huawei equipment.

One important, but often overlooked, facet of Huawei’s growth has been its position in its domestic market. The PRC has long prioritized wireless networking for its strategic aims, and Huawei was able to readily outmaneuver its competitors who were state-owned and state-run. Huawei is not quite a monopoly provider of wireless gear inside the PRC, but it often wields near monopolistic influence. The mobile operators, who are all state-owned, are strongly encouraged by the government to use Huawei gear and thus have limited negotiating power. This is a critical overlooked factor for the company – it is not well loved in many parts of the PRC economy. As much as it is held up by the (State-run) media as a model and a hero of the PRC’s modernization, in private many PRC companies are deeply distrustful of the company, and this applies across many sectors, not just telecom.

Huawei as Venture Capitalist

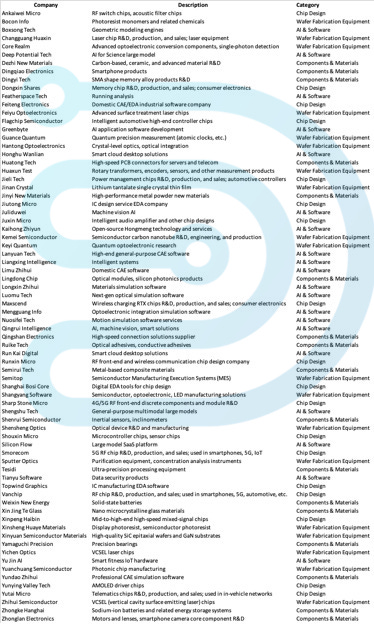

Hubble is Huawei’s venture capital arm. In 2021, a contact in Shenzhen sent us the list of Hubble Capital’s portfolio companies. That list had ten names on it. Below we have a more recent list, from 2024 with Hubble’s portfolio companies. This list has 74 names on it, and we are fairly certain that it is missing a lot of Hubble’s investments. We have heard reliable estimates that puts Hubble’s portfolio at 200-300 investments. Huawei founded Hubble in 2019 just as US sanctions began, with a clear goal of developing workarounds for those sanctions, and it looks like its scope has widened with each successive round of restrictions.

Hubble has the widest scope of any venture investor we have seen covering: fabless chip design companies, optical and networking companies, electronics manufacturing, EDA, enterprise SaaS, wafer fabrication equipment (WFE), materials and beyond. We know the fund has also invested in a wide range of AI-related end markets including robotics, autonomous vehicles and (likely) drones.

Hubble keeps a very low public profile. We have not been able to find a web page for the firm, nor can we find any mention of Hubble on Huawei’s site or its filings. We conducted an extensive Chinese language search on Hubble, which turned up a number of links, only to find all of these links were blocked to web users outside of the PRC.

Hubble reportedly has RMB 300 billion (US$42 billion) of assets under management, although it is unclear how fully this is invested. Hubble’s management team are all high level Huawei executives, and press reports often describe Hubble as just the corporate vehicle where Huawei houses its investments. Investment decisions appear to be made by business unit teams inside Huawei. If true, this in itself is notable, as very few corporate venture teams are able to so closely align corporate venture with business unit objectives, and none have ever done it on this scale.

Selected Portfolio Companies of Hubble Capital

Huawei as Semiconductor Expert

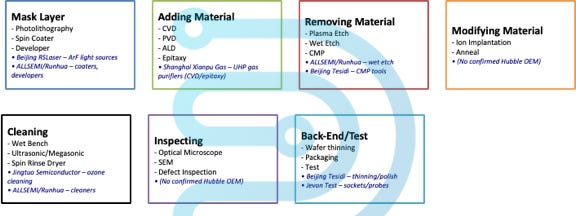

Tying this all together presents a fairly stark picture. Huawei has invested across the entire breadth of the semiconductor manufacturing stream. Below we lay out a simplified map of that process with Huawei investments mapped in blue. Huawei is present in all but two of those areas, and we are fairly certain they have multiple investments in both, as well as press reports indicating that Huawei’s foundry partners are still able to purchase US and EU tools. Huawei seems to be taking the broadest approach possible for building out this chain – investing directly via Hubble, purchasing tools from the rest of the world through third parties, and working with domestic PRC companies. In the latter case, we think Huawei is not only purchasing domestic tools but also likely providing engineering support to bring those companies closer to global levels of productivity.

Huawei and Hubble Investments Across the Semiconductor Fabrication Process

Huawei is pursuing the same approach at the fab level as well: they appear to be sourcing chips from TSMC through thinly veiled third parties; supporting domestic foundries like SMIC and Huahong – both with financial and engineering support; and multiple press reports indicate they are building their own fabs.

Put simply, Huawei is seeking to create its own entire semiconductor supply chain from wafer fabrication equipment (WFE) to fab and foundry all the way to design, test and packaging. Looked at another way, it is seeking to replicate ASML, Lam Research, Applied Materials, TSMC, Qualcomm, Nvidia and Ericsson, as well as many of their sub-system suppliers.

The scope of these ambitions raises two questions: can Huawei accomplish all this and can everyone else keep moving ahead to maintain their lead?

All of this is incredibly challenging. The PRC’s WFE and foundry industries have lagged the West despite a decade of investment. Semiconductor manufacturing encompasses a massive supply chain. For example, the leading ASML Twinscan EXE:5000 family of EUV lithography tools cost $300+ million a piece and have 100,000 components from over 1,000 suppliers. Many of those components have only one supplier, such as the light source from ASML itself and the optics from Zeiss. Replicating all that across a supply chain with dozens of different tools is hard to contemplate let alone execute. That being said, Huawei has a long history combining reverse engineering and internal engineering talent. In Silicon Valley terminology they are solving a 1 to N problem, where they have access to ample research done by those who solved the 0 to 1 problem. All in all, we are inclined to assume they can achieve advanced semiconductor manufacturing advances, and probably sooner than most expect. When the US government first imposed broad restrictions on PRC access to advanced WFE in 2022, we forecast that it would take the PRC supply chain ten years to bridge that gap. But Huawei started that work in 2019, and have made more progress than anyone expected them to. To cite the example above, they claim to have a working light source for EUV and may have found an alternative to Zeiss, as well as the many other advances elsewhere in the supply chain.

Will Huawei’s tools end up being as good as those from competitors? Probably not soon, but will they be ‘good enough’? Very likely. The progress of their Ascend chips produced in conjunction with foundry SMIC is a good case study in this. Those chips and the manufacturing process they come from are fairly unsophisticated compared to the best TSMC has to offer, but they are viable for Huawei today. Even if their AI accelerators are 1/16h as powerful as the latest from Nvidia, Huawei likely has the resources to build 16 data centers to compete. We are obviously oversimplifying this, but our point is that Huawei can accomplish many of its goals without being at the leading edge or state-of-the-art.

Recall that Huawei is not exactly trying to build a commercially viable alternative to the TSMC ecosystem, there are government policy goals behind them. While the company claims they get no direct support from the PRC government, at the very least they do effectively have zero cost of capital, and probably a large degree of indirect support as well.

So we think it is very likely that before the end of the decade Huawei, or one of its close partners, will unveil a fully domestic PRC leading edge fab.

However, that term ‘leading edge’ is doing a lot of work. Foreign WFE makers and foundries are not standing still. Take the example of advanced semis packaging. These processes have become a critical element for manufacturing AI systems which combine memory and logic into a single system. There is no clear indication that Huawei has made much progress here. These processes are still very new even to TSMC with considerable R&D work still taking place. Over time, Huawei will be able to solve this one, but they are running after a rapidly moving target.

Huawei as Cloud Service Provider

Throughout this piece, we have focused on Huawei’s successes, but it is important to note that they are not perfect and have encountered their share of setbacks. One such area is in the field of cloud computing. Huawei has operated a public cloud service provider (CSP) for over a decade. They sought to replicate the success of Amazon’s AWS, but here they encountered insurmountable competition, not from the US giants from their domestic peers. Huawei’s entry into the CSP space faced considerable pushback from the PRC’s other cloud providers, such as Alibaba and Baidu. Most notably, the telecom operators strongly objected to Huawei’s ambitions here as it impinged on their core networking assets. As a result Huawei Cloud never broke into the top tier of domestic CSPs. They have seen some success in their core overseas telecom markets, but even here they struggled as telecom operators have shown deep ambivalence towards the cloud computing business and competition from the US was much fiercer. All of this took place years ago, and we imagine that if Huawei rekindled its ambitions here it might enjoy greater success domestically. Our best guess is that they will make a renewed push as a provider of AI compute running their own accelerator chips. So today Huawei has not really become a major cloud service provider, but they may make a comeback as a neocloud.

Huawei as Automotive Software Leader

Probably one of the most powerful of Huawei’s initiatives is in the field of autonomous and electric vehicles (AV and EV). Huawei emerged from its dark period as a leading provider of software for cars. The kernel of this business came from their efforts to relieve their reliance on foreign operating systems (OS), especially Android for mobile and Windows for PCs. They unveiled Harmony OS three years ago and it is has seen some adoption on Huawei phones, but more importantly served as a springboard for their move into in-car operating systems for driving assistance, and then for full autonomy. Huawei’s goal appears to be a provider of the entire software stack for automobiles.

Huawei offers this solution in a variety of offerings ranging from component and point solutions all the way through to joint ventures designing and marketing cars. The company currently has four joint ventures making EV lines with four different PRC auto OEMs. Under these JVs, Huawei typically provides all of the software, much of the design and electronics componentry, and leaves manufacturing and distribution to its OEM partners. At a step below this, Huawei positions itself as a “Tier 1” supplier, or a leading supplier of automotive software to another half dozen auto makers. The company claims to have its smart driving system in 20 models currently and has forecast that by 2027 over 27 million vehicles on the road will be running on their software. Huawei also provides software for three foreign auto makers (VW/Audi, Mercedes and Toyota). These OEMs use Huawei software for cars made and sold in the PRC, but are reportedly considering using Huawei software for vehicles exported internationally.

Huawei faces a lot of competition here. There are a half dozen PRC companies in the vehicle software space, and many of the PRC EV OEMs are developing their own software, including companies Huawei currently counts as customers.

So while Huawei does not hold the commanding heights in this field the way it does in networking and semis, it has proven immensely capable and looks likely to remain one of the leaders in the field as PRC EVs continue their expansion around the world.

Huawei as a Company

As should be clear, Huawei holds considerable influence across some of the most critical segments over the technology industry, but we also think it is important to look at it as a company. While Huawei has not, and probably never will, offer its equity publicly, it did issue public debt, and so we can look at the company from the vantage of the financials it discloses as part of those filings.

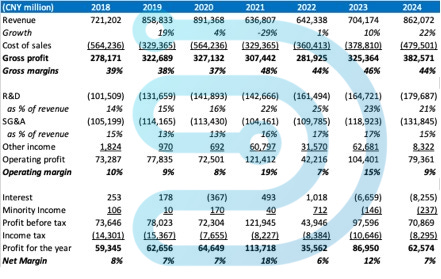

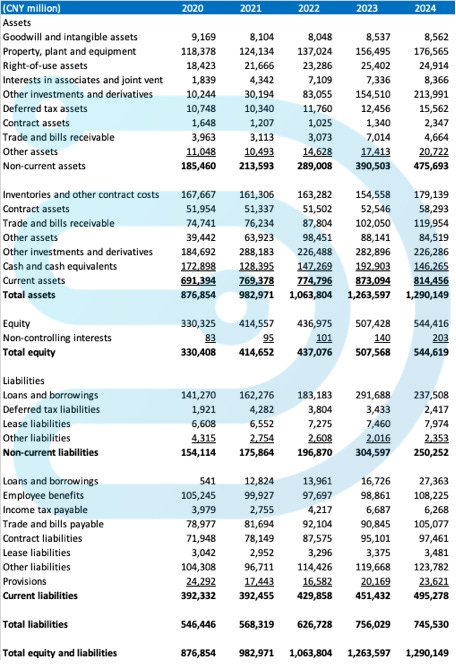

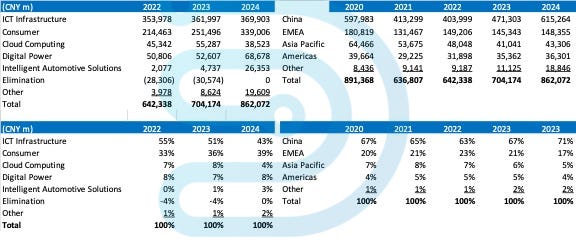

This is Huawei’s annual income statement through 2024.

We can see the impact of the US sanctions through these numbers, with revenue declining almost 30% in 2021, only to recover to RMB 864 billion (US$121 billion) in 2024. Gross margins of 44% are not terribly exciting but better than many of its peers in the equipment markets that were once its core business. The company widely touts its heavy R&D expense, demonstrating how much it spends on innovation. At 21% of 2024 revenue that figure is higher than many companies, but not by an order of magnitude. Nor are its operating and net margins particularly eye-catching. Its balance sheet and working capital metrics, printed below, tell a similar story. The downturn is clear, but the company has largely worked through the worst of it.

Huawei’s operating segments are a bit more interesting. Here we can see the company is still heavily reliant on domestic sales, a figure which actually fell during the downturn but has now resurged. We can also see the growth of the company’s auto business which is up 13x in just two years.

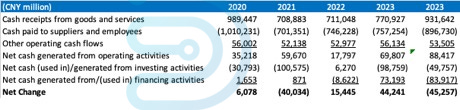

And for completeness, here is the company’s statement of cashflows, in its entirety.

What is most notable to us about these numbers is what is not shown. This company has invested around RMB 300 billion since 2019, where does that appear in these figures? There is a balance sheet item “Other Investments and Derivatives”, whose footnote indicates the company holds just under RMB 200 billion in “equity securities and beneficiary positions”, which looks about right, but could also reflect treasury positions. Moreover, where does that flow through the statement of cashflows?

Unfortunately, this is all the data available. Huawei’s annual reports only lists about two dozen subsidiaries and no detail on its venture investments. Given the extent to which Huawei tries to tightly control the flow of information about it, these financial statements can be useful. But we know that PRC companies commonly have vast networks of affiliates and complex corporate structures, so we have to imagine that Huawei has a much wider organization than we can see here.

Conclusion

Bringing all of this together, we increasingly have come to think of Huawei as something more than a company. It is easy, and all too common in the US press, to dismiss PRC companies merely as fronts for the PRC State or the Party, but that greatly oversimplifies the nature of competition and corporate structures there. Huawei is not a state-owned enterprise operating as an employment program or serving some local political objective. This is one of the most competitive companies in the world, that can hold its own against international giants. That being said, as much as it operates on commercial principles, we think the company uses all its profitability as just one way to measure its productivity, rather than an end goal in itself. We think it is a stretch to say that the PRC controls Huawei, if that were true Huawei would more closely resemble the many SOEs out there, with dusty offices crowded with over-staffed ranks. However, we do think it is accurate to say that Huawei’s objectives are tightly aligned with the government’s policies. We think the relationship mirrors US defense contractors in the 1950’s, or IBM, or United Fruit. Companies whose interests lined up with the US government’s policies, and maybe were available for the occasional more direct involvement, but critically they all had their own agency and objectives. In that vein, Huawei can be seen as the flagship or National Champion of the PRC’s electronics manufacturing export ambitions. Aligned, but independent.

The other critical factor is Huawei’s deep engineering talent. They are not perfect, their engineers cannot bend the laws of physics, but they are capable of building competent solutions to many of the most critical technical challenges out there. This holds particularly true in semis, where we think their vast network makes it likely that they are capable of advanced manufacturing breakthroughs much sooner than many expect.

At the same time, they are human. One of our favorite insights into companies can be found in the employee forums which are (very surprisingly) available on the open web (for now). The top headline on the page is currently “Win with quality, build a high-quality industrial chain”, but mostly deals with employee questions about where to get good dental care, things to look for when buying a used car and whether taking an overseas hardship post will help a career. These are ordinary people with ordinary concerns.

Beyond the entertainment value of this site, it is a reminder that Huawei is not some mythical entity. It operates in a very competitive market. Despite the immense influence it wields, in its home market it has its rivals. No company gets as big as Huawei has without creating deeply hostile foes. In international markets, or facing off against foreign companies, they may present a unified front, but there are far more companies jealous of Huawei’s success inside the PRC than outside.

Narrowing this down to semiconductors, we think Huawei’s resurgence poses a serious long-term challenge to the entire global semiconductor supply chain. PRC companies currently have a plurality in manufacturing share for trailing edge capacity, a share which could grow to an outright majority this decade if all the planned expansions materialize. If Huawei is able to break through in leading edge manufacturing, it would present serious competition and probably alter the geopolitical balance.

If you like this content you should listen to our podcast.

Great analysis!!! Just finished reading Apple In China - don't under estimate the role of PRC government/CCP in their domestic companies (as Apple has learned). And, in the space of one week (having read your post last week) - China bans tech companies from buying Nvidia’s AI chips AND Nvidia and Intel announce their companies will jointly develop multiple new generations of x86 products together - my head is spinning. We live in interesting times!