D2D Cont'd: The Quest for Returns

How much capex is enough?

Week In Review

We thought this was going to be a quiet week. We only had one company report earnings, AMD, and they are usually pretty straightforward. But the universe had other plans.

Geopolitics had its way with semis this week. A big focus on the otherwise standard AMD call was the timing of their return to selling products to the PRC. AMD and Nvidia had both been restricted in their sales of GPUs there, both had those restrictions removed. And so now everyone wanted to know when sales could resume.

Then, Wednesday afternoon someone forwarded us a letter by Senator Tom Cotton to the Intel Board criticizing the company’s CEO for his ties to the PRC. The letter seemed to specifically reference the $140 million fine leveled against Cadence for deals with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) signed when Tan was CEO of that company. We can be forgiven for not thinking about that letter much, as there is a lot of noise in the industry lately, and this seemed just one more performative act that would fade with whatever chaos the next news cycle brought. We should have known better.

Thursday morning, the President tweeted that Intel’s Board should remove its CEO Lip Bu Tan because of his ‘conflicts’. The President did not specify which conflicts he was referring to, and it is unclear if Senator Cotton’s letter played any role in this. As we wrote in our note that day, while this is not good for Intel, it at least indicates the US government is thinking about Intel, and maybe, possibly negotiating a deal.

Intel did itself no favors by waiting all day to put out an incredibly generic press release. This was followed by a letter from the CEO to the employees reassuring them in equally bland terms. The whole situation read like the company was once again in turmoil.

But then one more shoe dropped. Reuters published a story claiming that yields on Intel’s current 18A manufacturing process were “10%”, a woefully low level less than six months from volume launch. We should note our conversations with the channel are a bit different. We believe Intel is telling its customers that it will be shipping Panther Lake CPUs on time. If yields were really that low, they would (probably) not be telling this to customers whose trust Intel badly needs to regain. We think these two data points can be bridged by that word – yield. We believe Intel is facing lower than expected parametric yield on its parts. Intel can produce a lot of chips, but these have bugs which mean that many of the parts are ‘binned’ at lower performance levels. Without getting into the details this likely means that Intel has enough parts for its customers but an excess of lower performing chips which they will have to mark down to sell. One way or another it sounds like Intel’s gross margins are going to come under pressure later this year.

The Quest for Returns

Last month, the big US Internet companies all spoke to their massive capex figures. Since the majority (maybe the vast majority) of this is being spent on semiconductors for AI, we have been thinking a lot about what kind of return these companies can expect from their investment. Are they generating sufficient profits to justify the continued spending? If not, how long will they maintain it?

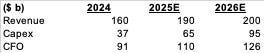

Let’s do this hypothetically, Acme Internet, a leading social/mobile/AI platform is doing well but is spending a lot on capex. Here are our hypothetical financials:

Acme’s Hypothetical Financials

Acme’s capex is almost tripling in three years to capture all that AI goodness. This is faster than forecast revenue growth of 12% (CAGR). Cashflow from operations (CFO) is improving at a better clip, 18%, because AI is improving performance and reducing costs, but still trails capex growth over this period of 60%. So that is not great.

Another way to look at this is to break down capex’s impact on the the income statement. Acme accounts for its AI servers over a 5.5 year depreciable life. Already we have a problem. With new Nvidia gear coming out every year, and the amount of work AI servers are doing, we think a three-year life is probably more accurate. It is worth noting that all the major hyperscalers increased the depreciable life of their servers since the AI boom started. Maybe they will repurpose last year’s training GPUs to run inference next year…

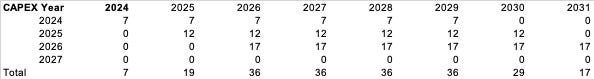

Even at 5.5 years, the incremental depreciation cost is significant. We built this handy depreciation revolver to demonstrate this point. (And yes, there is a narrative violation here, because we had ChatGPT build out the excel formula for this, but we got that for free.)

Acme Depreciation Revolver

Depreciation ($b)

By 2026, the company will be facing $36 billion in additional depreciation expense – that works out to 28% of cash from operations.

Over this three-year period, Acme will spend $200 billion on capex. To generate a 10% return on that would require the company to generate an extra $20 billion in increased revenue and/or cost reductions, every year for 5.5 years, above existing growth. Nothing in these numbers looks like the start of that kind of acceleration.

And all of this assumes the capex goes down at the end of this three-year period, and that the company does not have to keep investing in ever newer GPUs.

We think the point is clear, there is no purely financial justification for this spending. But these are smart, immensely successful people. Why are they investing with no clear financial gain in sight?

We see two possible answers to this question.

The first is the company believes that somewhere past our forecasting ability they will have some incredible breakthrough. Call it AGI or Super Intelligence or Lip Syncing Robots, something big that will be meaningful enough that we can throw out all the finance textbooks. That is possible. The underlying technology is certainly improving at an incredible clip. But this a faith-based line of reasoning, belief not logic is driving this decision making. In fairness, we call belief that becomes success vision, but it is hard to see things materializing along these lines soon.

The other take is that Acme sees Google, Meta, Amazon, Oracle and all their other competitors spending in a similar fashion. The company could reasonably argue that AI is a major shift in technology and they have to invest heavily to fend off their established competitors as well as any emergent ‘start-ups’ like OpenAI.

This argument is both reassuring and unsettling. It is reassuring in that there is logic behind it, and it implies that there is a finite limit to the investment. Once AI stabilizes the investment can taper off. But it is unsettling in that there is a lot of advanced game theory embedded in this argument. When everyone saw Microsoft investing heavily in AI in 2022, the others rushed in, without necessarily knowing what they were rushing towards. So at some point if one of the major spenders says they are done spending, the others will all wonder what that first mover sees and stop spending too.

We do not want to be alarmist about this. There are no signs of an imminent collapse in AI spending – quite the opposite. We do not even think many of these companies are spending much time thinking about these numbers. We also think AI can eventually develop some truly incredible offerings, the kind that would justify this expense. But that is a faith-based argument, and even with that sentiment, we do not think those big gains are coming soon.

If you like this content you should listen to our podcast.

The ROI calculation misses the defensive value of AI capex. These investments aren't just about generating returns 'above existing growth', they're table stakes to protect existing revenue from AI-native competitors who would otherwise cannibalize the core business.