D2D Cont'd: Jensen Math Meets GAAP Accounting

Nvidia faces growing competition. To address this, the company has been leaning on a variety of mechanisms to adapt.

We need to look at Nvidia’s financials in the light of the broader AI market. The company is an important player in the flow of fund around AI data center spending. It is also facing a growing tide of competition.

Last week, the Internet was full of all accounting theories around Nvidia, which we will address. We do not see anything malicious taking place. Instead, we see a company that is caught up in the rush to accommodate its growth, and the rush of the AI Boom has led to a fairly opaque accounting of the foundations underpinning the growth of AI compute. Put simply, we think Nvidia faces growing competitive pressure and has been leaning hard on a variety of sales mechanisms to adapt. These measures are not fully reflected in financials, but they are already material and look likely to grow significantly next year.

Working Capital

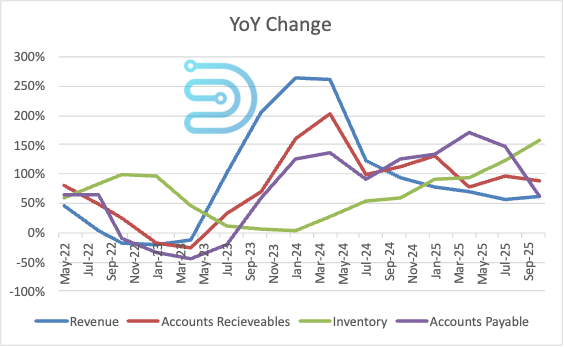

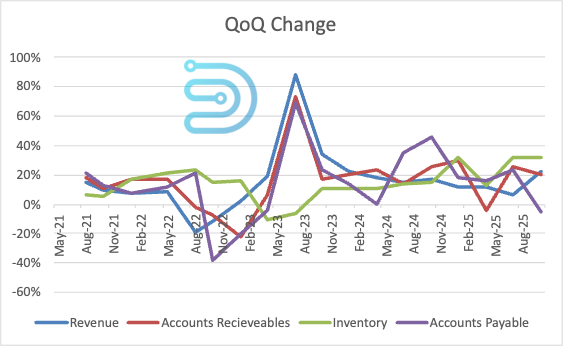

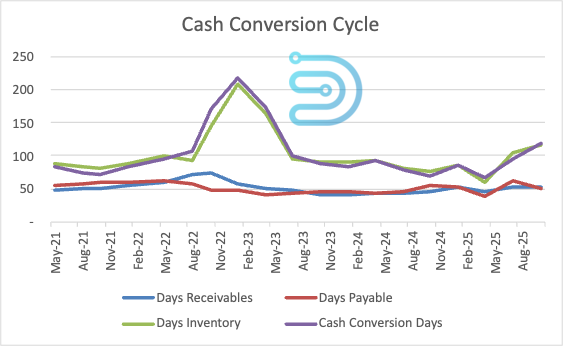

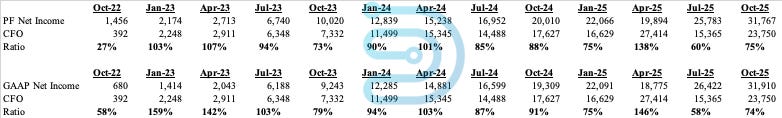

Since the company reported earnings two weeks ago, its working capital has garnered considerable attention online. The company’s inventory has grown considerably over the past two quarters. Days of inventory went from 59 in Q2 to 117 in the latest Q4 numbers, driving the cash conversion cycle from 66 days to 159 days.

So, something is going on here, but there is a plausible explanation for it. The company is ramping Blackwell systems, and it makes sense that they would be taking on inventory as they marshal shipments to customers. We saw something similar in early 2023 as the company ramped up shipments of Hopper systems. If that cyclicality holds, we could see inventory grow even further next quarter. Of course, back then, revenue growth was accelerating, and now revenue growth has slowed considerably.

Year-on-Year change in Working Capital

Quarter on Quarter change in Working Capital

Cash Conversion Cycle (Days Inventory + Days Receivable – Days Payable)

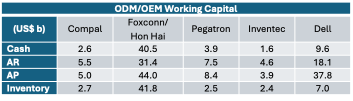

One quirk of Nvidia’s go-to-market motion is its relationships with the ODMs. We wrote about this a few months back. Much of the time, Nvidia sells its products to ODMs, who then package them up and re-sell them to end users like the hyperscalers and the neoclouds. While an undisclosed portion of sales go directly to the hyperscalers, the majority of Nvidia’s revenue goes through the ODMs. This presents a challenge to the ODMs as the working capital needs associated with a data center worth of Nvidia parts is significant, even for the largest Taiwanese ODMs. We think this is the most likely cause of Nvidia’s inventory build-up, holding onto its systems to ease the flow of payments through the downstream supply chain

Net Income Conversion

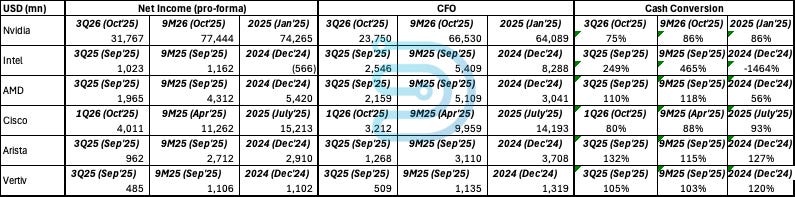

Another potential concern is the company’s conversion of net income to free cash flow from operations. The tables below show this ratio. We also compared this figure to some of Nvidia’s semis and AI complex peers.

Nvidia Cash From Operations/Net Income

Net Income Conversion Comparison

We see the concern here, with Nvidia’s conversion ratio down notably over the last two quarters. However, the company’s peers also vary widely. On a historic basis, the latest figures are well within Nvidia’s normal range, and are not even close to the lowest rate. We think this is largely explained by the company’s working capital cycle noted above.

Nvidia’s Balance Sheet

Nvidia has a fairly clean balance sheet. As of the latest quarter, they had gross cash of $60 billion and debt of $8.5 billion. With the hyperscalers taking on growing debt loads to fund their capex, Nvidia has so far kept its leverage fairly low.

That said, there are a number of items on the company’s balance sheet that merit further attention.

For starters, the company has co-signed an $860MM lease obligation for a neocloud, but this partner has left $470MM in a restricted escrow account, providing a fair degree of risk mitigation for Nvidia.

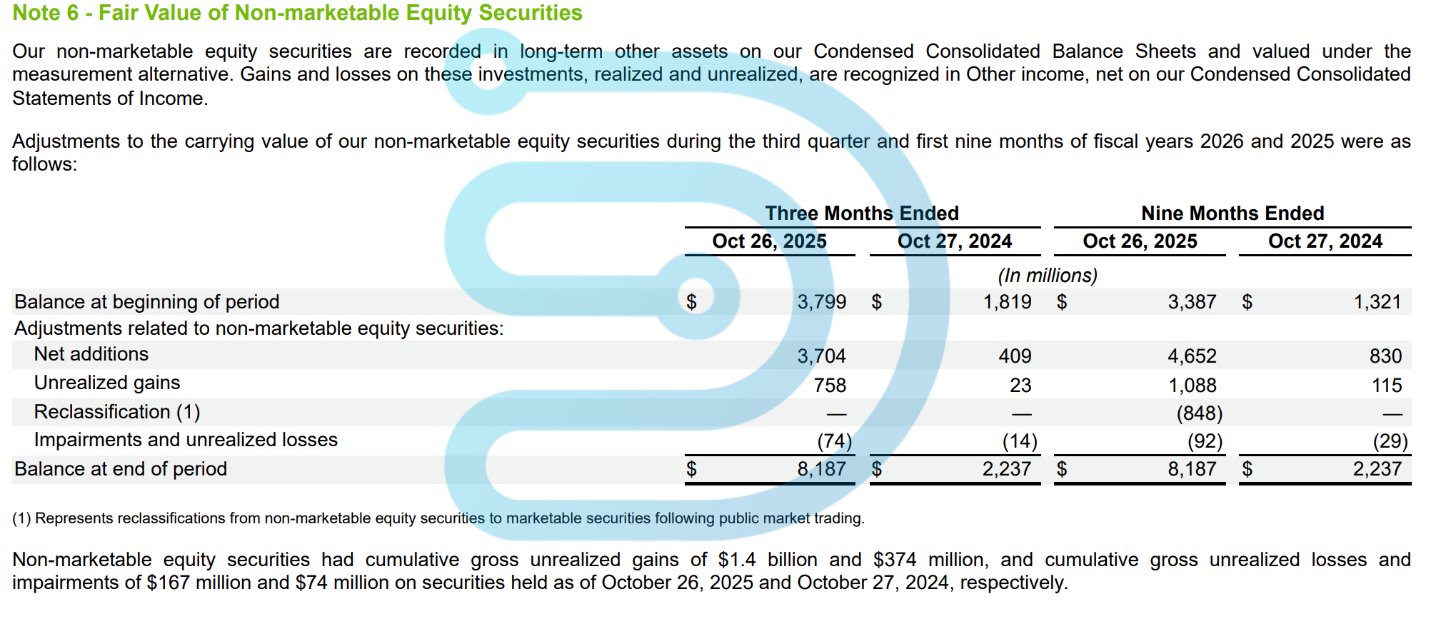

The company has also made a number of investments in customers as well as “commitments” to others.

Nvidia’s Investments in Private Companies

Nvidia carries these investments at $8.2 billion as of the latest quarter. Again, this is fairly small in the context of its operations, but it grew considerably this quarter, tripling over the past 9 months, and is likely to grow even more next year. Nvidia has committed $5 billion to Intel, $10 billion to Anthropic and $2 billion to other parties. And then, there is OpenAI. Nvidia has said it will invest $100 billion in OpenAI over the next few years. It is important to note that the two companies have only signed a letter of intent; this deal is not finalized. Nvidia can reasonably argue that these investments will pay for themselves as those companies raise more outside money and use the proceeds to buy Nvidia systems. Nonetheless, the scope of this effort is growing considerably, which we think speaks to the growing competitive market Nvidia faces.

Cloud Compute Service Agreements

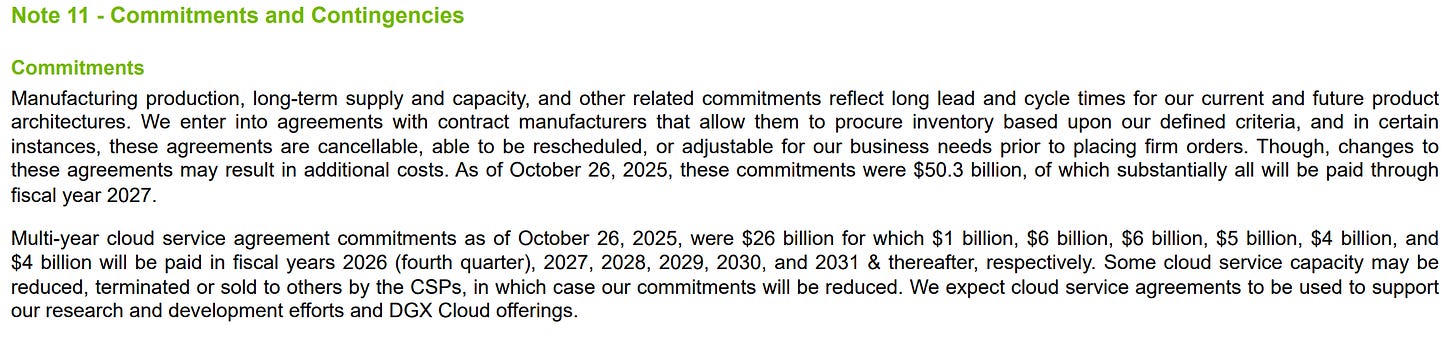

Which brings us to Cloud Service Agreements and Note 11 in Nvidia’s financials.

Nvidia Cloud Compute Service Agreements

The company now has $26 billion of what appears to be pre-paid cloud compute expenses. The company says it will use these for “R&D and DGX Cloud offerings”. We do not think this entirely explains this item.

To put this in context, the company is on track to spend $18 billion this year for R&D. Since this includes salaries, test, foundry expenses, etc., it is hard to see how they would need that much cloud compute for R&D purposes. All semis companies use some amount of cloud compute, but we know that these expenses tend to be orders of magnitude smaller, tens of millions of dollars a year for simulation, for example. Nvidia also operates its own data center, and we imagine much of their compute work can be done there.

As for DGX Cloud, we could write an entire other note on Nvidia’s Software as a Service (Saas) offerings, but the short summary of that is that these efforts are minor and the company has said they do not plan to grow this into a meaningful revenue source. Even if the company did plan to offer some form of SaaS, this would not require anything near this much cloud compute.

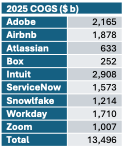

The table above shows total cost of goods sold for some large, cloud-based SaaS companies from their most recent fiscal year. Not all of this expense goes to cloud computing. Next year, Nvidia will have the option for $6 billion in cloud compute, which is at least double what the largest company on this table spends on cloud computing. In theory, the company could be planning to become a foundational AI model lab in their own right, but even that would not explain this amount fully (aside from the issue of placing it into competition with all of its major customers).

Instead, we think it is much more plausible that this amount recognizes the “backstops” the company has put in place with a number of its customers. Under these arrangements, companies which buy Nvidia systems get obligations that Nvidia will buy a certain amount of excess capacity those companies have running those Nvidia systems.

We have known of these arrangements for some time; they appear to be common practice for both Nvidia and AMD. We have evidence of them from Coreweave filings.

Corewave 8-K September 15, 2025

Item 1.01 Entry into a Material Definitive Agreement.

On September 9, 2025, CoreWeave, Inc. (the “Company”) and NVIDIA Corporation (“NVIDIA”) entered into a new order form (the “Order Form”) under the existing Master Services Agreement (“MSA”) dated as of April 10, 2023, which has an initial value of $6.3 billion, that establishes an arrangement with respect to the sale by the Company of reserved cloud computing capacity to its customers and provides NVIDIA access to any residual unsold cloud computing capacity. Under the terms of agreement, in instances where the Company’s datacenter capacity is not fully utilized by its own customers, NVIDIA is obligated to purchase the residual unsold capacity through April 13, 2032, subject to any termination described below and satisfaction of delivery and availability of service requirements. The Company has determined that the MSA is a material agreement within the meaning of Item 1.01 of Form 8-K because the MSA is no longer immaterial in amount or significance. The MSA will remain in place until either all outstanding orders under the MSA are expired or terminated, or the MSA is otherwise terminated in accordance with its terms. Either party may terminate the MSA (and any order thereunder) (i) upon 30 days’ written notice to the other party of a breach or (ii) if the other party becomes subject to a bankruptcy petition or other insolvency proceeding, receivership, liquidation or assignment for the benefit of creditors and such proceedings are not dismissed within 90 days. The MSA contains customary provisions regarding representations and warranties, indemnification, and limitations on liabilities. In addition to the MSA, NVIDIA supplies the Company with NVIDIA GPUs and is a stockholder of the Company.

The foregoing description of the MSA is qualified in its entirety by reference to the text of the MSA, a copy of which will be filed as an exhibit to the Company’s Quarterly Report on Form 10-Q for the quarter ending September 30, 2025.

Coreweave’s 10-Q includes a link to that the MSA, which resolves to an S-4 the company filed as part of its Core Scientific acquisition attempt, but the relevant details have been redacted.

Coreweave S-4 September 25, 2025

2. SERVICES.

a. Access to the Services. Subject to compliance with all the terms and conditions of this Agreement, Customer has the right to access and use the Services (which includes provision of the Services to End Users), with or without Customer Applications (including charging End Users for the foregoing, as determined by Customer), except that support and provisioning of the Services will be between Customer and CoreWeave. CoreWeave will provide the Service in accordance with the service level objectives in Exhibit B. Customer may provide End Users with administrative permissions to specific compute resources of the Services. [*]

With respect to CoreWeave owned and operated hardware: CoreWeave is responsible for managing NVIDIA and other CoreWeave customer demand across its infrastructure. NVIDIA will not have the right or ability to [*]. CoreWeave must not, at any point in time, dedicate more than [*] of available customer capacity to NVIDIA (the “[*] Rule”); such capacity being measured by each server type.

The timing of this lines up with Nvidia’s $13 billion sequential increase in cloud compute services, but only explains half of that increase.

It is also important to remember that Coreweave asserted this agreement as part of its argument for why Core Scientific shareholders should subscribe to the Coreweave acquisition. Coreweave sees this as a valuable agreement. By our math, Nvidia’s backstop for Coreweave would comprise 30% of Coreweave’s revenue, if Nvidia chose to use its allocation.

Nvidia does not recognize these agreements in its financials. The detail on the agreements is found in Note 11 of the company’s filings, and is explicitly not included in the balance sheet.

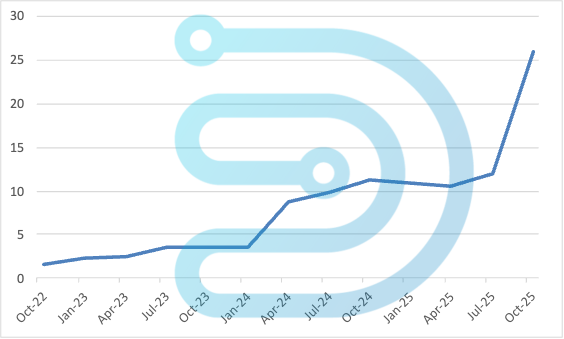

For historical context, Nvidia began reporting cloud compute service agreements in the footnotes in 2Q23, right before the AI boom started, and it has grown steadily since then.

Nvidia’s Cloud Compute Service Agreements ($ billions)

In one light, these sort of backstop agreements can be seen as normal course of business. A customer buys something from a vendor and the vendor agrees to be partially paid in kind by the customer. What is notable here is the scale of Nvidia’s usage.

With these agreements, Nvidia has essentially sold its customers a put on their capacity, the right to sell excess capacity back to Nvidia. We believe we are clearly in a grey area of GAAP rules. If Nvidia brought it onto its books, they could take the form of debt, or other obligations on the liability side of the balance sheet.

Instead of debt, we think this should be viewed as a form of discounting. We estimate Coreweave is going to spend close to $20 billion next year buying Nvidia gear. Nvidia backstopping $3.5 billion of that works out to an 18% discount. Nvidia can reasonably argue that they will not have to buy all of that capacity, but the risk is real. It is worth considering what would happen if the Nvidia backstop did not exist. Our take on the debt markets is that much of the financing for neoclouds is collateralized by its customer agreements. Nvidia is stepping up for a meaningful portion of that, which implies that at the very least, Coreweave would have to pay a higher rate.

Put another way, if Nvidia had to recognize its $6 billion in compute agreements as part of COGS, it would reduce gross margin from an estimated 72% to 68%, reducing pro-forma EPS from $6.28 to $5.97. Small in the context of Nvidia’s overall earnings, but still meaningful for a company facing intense investor scrutiny on gross margins.

Competition

We also want to address the news over last week about growing usage of Google’s TPU. We have long held that the most significant competition to Nvidia is the hyperscalers’ internal chips, with Broadcom helping to bring them to market. The surprise is the degree to which Google has become adept at promoting the use of TPU to third parties.

For certain (many) workloads, TPUs offer meaningful performance advantages against Nvidia, especially when evaluated at the system level where Google’s all-optical networking offers better bandwidth and latency. In many cases, networking accounts for 30%-40% of server total cost of ownership (TCO), and so taken as a complete system, TPU can offer real value against Nvidia, even including Google’s mark-up.

In fairness, there are some limitations with TPUs. First and foremost, their software frameworks still lag Nvidia’s CUDA et al by a good measure. While Google has made large strides in bridging that gap, the real barrier will be customers’ ability to port their workflows over. For companies with deep technical expertise (e.g. Anthropic, Meta), this is manageable, but for most other companies (i.e. the Fortune 5000), the cost of the move is likely prohibitive.

Another serious limitation is Google’s ability to sustain product and customer support. They do not have a great track record here, and the organization is still very internally-focused.

Netting this out, Google is unlikely to emerge as a broad-based merchant chip vendor, but they are a serious competitive pressure for Nvidia with some key customers.

PRC Sales Still in Limbo

Finally, we want to touch on sales to the PRC. As far as we can tell, the company is still hobbled by US political concerns blocking sales of its products (and AMD’s). Our checks indicate the company’s prospects were further dimmed by comments Jensen made to the US and PRC press last month. It is noticeable that he has been very quiet on the topic since then.

This remains a major weak point for the company. In our reading of PRC media, there is growing interest in Huawei’s solution, albeit not quite enthusiasm. Instead, we have seen a steady run of headlines suggesting that PRC companies are spending heavily outside of the country (e.g. Malaysia) to access Nvidia systems. These deals are constrained by PRC data export laws. For their part, Nvidia changed its definitions for reporting revenue by geography, blurring a picture already obscured by the extensive use of shell companies by PRC entities. So, while Nvidia is able to tap into some of the demand from the PRC, it is increasingly constrained by scrutiny from both countries.

Nvidia is in the unenviable position of having to walk a fine line where many of its actions risk one side or the other, which is giving PRC competitors room to reach scale.

Click here for full PDF report

If you like this content you should listen to our podcast.