D2D Cont'd - Intel and the Wide Open Barn Doors

Once again, we are questioning Intel's long-term fate

Intel reported this week and while the numbers were fine, they also seem to have sideways announced a major strategic shift in regards to the future of their fabs. On the call, and the accompanying 10-Q, the company indicated that it would only bring their 14A process into production if they can find an external customer who wants to use it. To be fair, their ultimate plan is not entirely clear, and they may be more committed to 14A than we inferred from the call, but much of the damage from this decision has already been done. We strongly disagree with this approach and worry about what it means for their future and the rest of the industry.

Some background. Intel’s current manufacturing process, 18A, is poorly understood by the market. Some saw it as the node that would save Intel, but we have long held that its value rest solely in its ability to keep Intel going long enough for them to reach the 14A process. On paper, that looks very competitive, arguably better than what TSMC will be producing at the time. The current process seems to be good enough for Intel’s internal products, but the company still lacks many of the other requirements of making 18A available to outside customers. Rocky, but stable. We will know more about this process as Intel releases products built with it later this year.

Regardless, 14A was supposed to be the real determinant. If 14A is as good as promised, and critically if the company can get yields on it, then the future of Intel Foundry would be viable, and maybe someday competitive. If 14A does not work, then Intel will fall off the curve of Moore’s Law, and no one who has fallen off has ever made it back onto the curve.

Which brings us to last week’s call. Four items alarmed us:

· The emphasis on “investing for demand”, a literal repudiation of “if you build it they will come”, and the direct implication that 14A may not happen.

· 14A is not in volume until 2028 or 2029 (which means 2029), later than we had expected and thus less competitive with TSMC.

· The lack of clarity around the strategy. Is this announcement some form of advanced public negotiation? Maybe. But if so, its delivery seems muddled.

· Probably most concerning for us was the CFO’s statement that “De-levering the company is our top priority”.

Intel’s new strategy holds that they cannot develop 14A without support from external customers. We understand the problem, it is expensive. By our rough math, they need about $80 billion in cash (opex + capex) to bring up 14A to first revenue. Cash from the product side only gets them about $60 billion of the way there, tack on some help from the US government, and the gap is still $10 billion - $15 billion. The math has not really changed since Pat Gelsinger was ousted as CEO, and his strategy seems to have very much been to call in every favor possible and dredge up that money somewhere. Not ideal, but also not so different from the hustle that every start-up has to go through. The money is out there, it was always just a question of finding a deal. But that approach is not possible if 14A is now in doubt. The 14A Field of Dreams needs a field.

Perhaps a big reason for the shift in outlook comes down to timing. From the call, 14A will not be in volume production until the end of 2028 or early 2029. Assuming it hits that schedule (a big if), it will enter production two years after TSMC’s A16 process, and roughly the same time as TSMC’s A14 arrives. That is not disastrous, but it is also not soon. At best 14A would be roughly comparable with what TSMC is shipping. Given the cost of ramping a new process, especially from an untested foundry, most customers would want a meaningful advantage to support it, and it is not clear 14A will offer that by the time it is launched.

To be fair, none of this is written in stone. We are interpreting a handful of comments, answers and three sentences in the 10-Q. It is possible that all of this language is part of a complex negotiation with someone. Many analysts read this commentary as an implied threat - “come support us or there will be no Intel Foundry as an alternative.” We certainly agree with the sentiment. Below we will discuss what this means for everyone else, but it is a potent threat. The only problem is we are not sure who is the intended target of the message. And by announcing it in this way it opens up the very real problem of why would anyone else adopt a process that Intel is willing to abandon? Designing a chip takes two years, and as noted, porting to a new process is an expensive proposition. If Intel cannot convince any big customers in the next year that 14A is worth the trouble, then no one will pick it up. Intel may have been trying to send a message to someone, but for everyone else it sounded like Intel is giving up. Or at least giving no reason to even consider 14A.

Finally, the sum total of our fears arrived with CFO David Zinsner’s comment that “De-levering the company is the top priority.” From a financial perspective this makes sense but only in the most short-term analysis. This kind of financial benchmark implies that everything else has to fall by the way side – things like regaining manufacturing excellence and long-term strategy. Intel just went through a decade of prioritizing short-term financial metrics which did not leave the company in a good place. To revert back to that mindset now strikes us as tragic, a major missed opportunity to invest for the future.

And this is where everyone else needs to take note. If Intel truly abandons its plans for 14A it will also exit the foundry business. And absent a major change at Samsung, TSMC’s effective foundry monopoly will become an actual Monopoly in leading edge semiconductor manufacturing. As much as TSMC is generally viewed as being very customer friendly, absent a competitive check, it will eventually raise prices. There are already multiple press reports that it is looking to raise prices for its N2 process next year, with figures as high as $50,000 per wafer out there. What would stop it going to $100,000/wafer for A14?

This will fundamentally alter the semiconductor industry.

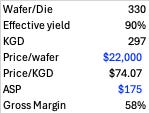

Below is some very simplified math. Let’s say there is a fabless company that today has a chip which can fit 300 die on a wafer, that ends up yielding 270 known good die (KGD, or working chips). For volume manufacturers today, they are probably paying around $22,000 a wafer. If they price the chip at $175, they make a reasonable 53% gross margin.

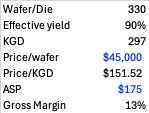

At $45,000 per wafer that goes to a decidedly not reasonable 5% gross margin.

In this example, a $47,250 wafer price is 0% margin. And since Moore’s Law is slowing that price increase for the new process probably only yields 10%-15% performance gains, which does not make the math much better. At these levels, it will not make sense for many companies to move to more advanced nodes. We think of this as the true end of Moore’s Law.

Many companies will be able to weather some amount of pressure. Nvidia, for instance, has ample margin to give up. But many others, even large companies, will not. Perhaps, the companies most affected by this will be aspiring internal chip projects at the hyperscalers. They do not enjoy the volume discounts of the large merchant chip designers. For many of them, designing their own silicon has been an attempt to save cost versus buying from merchants vendors, but at these level that math no longer pencils.

The real tragedy in all of this is that it does not have to be this way. There is a perfectly viable commercial solution to Intel’s problems. We think a consortium of chip designers need to step up and make an investment into Intel. Companies like Apple, Qualcomm, Amazon and Microsoft along with many others could easily pony up $20 billion, for a 20% a stake in Intel, funding the development of 14A. This is exactly what the industry did 15 years ago when ASML needed funding to develop the EUV systems upon which we all depend day. Ironically, that investment was led by Intel. Our point here is just that this has worked well in the past.

Absent something along these lines, we think Intel is on the verge of abandoning advanced manufacturing entirely. If that is true, they should act now. Without 14A, their fabs are now at peak value and the clock is ticking downward.

If you like this content you should listen to our podcast.

The plural of die is dice