D2D Cont'd: Intel and the Foundry State of Play

A deep dive into Intel and the current state of semiconductor foundries

Executive Summary

Intel has arrived at the crossroads. It needs to decide if it will continue to manufacture semiconductors. To stay on the path of Moore’s Law, we estimate it needs $15 billion to $25 billion, and it is not clear who will supply that. Instead, if they choose to abandon manufacturing they need to move quickly to save the Product side of the company.

As much as most observers have already written Intel off, we think it is critical for the semiconductor industry, that Intel stay in the game. Without Intel, and Samsung Foundry on shaky ground, there is a non-zero chance that TSMC becomes a true monopoly. And like any monopolist it will eventually raise prices to the point where many customers will choose to delay moving to advanced nodes, which will slow down the entire technology industry.

Semiconductor Manufacturing Background

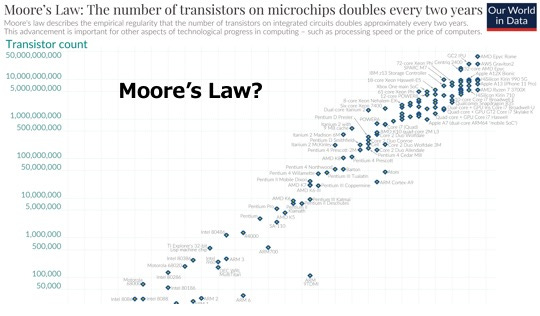

The semiconductor industry is designed to take advantage of “Moore’s Law” which holds that transistor density of semiconductors doubles every two years. The less mentioned corollary to Moore’s Law (sometimes called Rock’s Law) holds that the cost of building semis fabs capable of producing at that leading edge goes up almost as quickly. Today, a leading edge fab costs about $20 billion, most of which goes to tooling. As a result of this cost, Moore’s Law is slowly coming to an end.

Moore’s Law

Source: Our World in Data

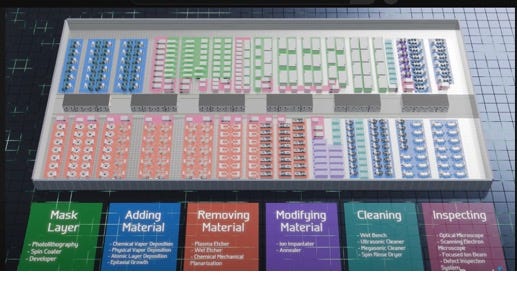

Manufacturing semiconductors is incredibly complex. Fabs process wafers through hundreds of steps involving several dozen different tools, each of which pushes the boundaries of engineering. The ability to produce at the most advanced nodes requires deep understanding of each of these systems and very fine-tuned designs of systems for running wafers through each of these steps. Our point being that making semis is not just a matter of buying some tools, it also requires a high degree of human capital capable of designing entire processes.

Overview of Fab Layout by tool top

Source: Branch Education

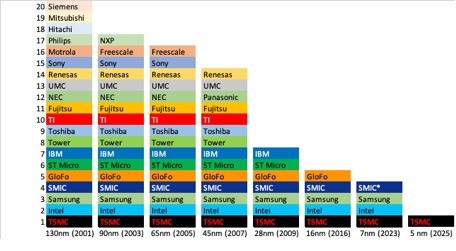

As a result, the number of companies capable of participating in the race has been declining for years.

Number of companies producing at each node over time

Source: Handel Jones, IBS-Inc, Seaport

Foundry State of Play

Today, there are three and a half companies capable of manufacturing semiconductors with “advanced” process nodes – TSMC, Samsung, Intel and maybe (maybe) SMIC in the PRC. Of these, TSMC is the leader both in terms of revenue but also in terms of technical capabilities, and they have a large lead. The history of semiconductor manufacturing is marked by important technological transitions which tend to shake out contenders. Twenty years ago, there were 20 companies manufacturing at the leading edge, but that list has been winnowed down by the increasing cost and complexity of manufacturing. Most recently the transition to Extreme Ultra-violet lithography (EUV) seems to have marked another of these industry milestones. TSMC has mastered mass production using EUV systems, the others are still in the learning phase, and it is unclear if they will make it out. Another critical element in this business has been the need for third party customers. At the leading edge, no company can operate fabs solely for their own business (aka the IDM model), they need to operate foundries, offering manufacture for outside customers.

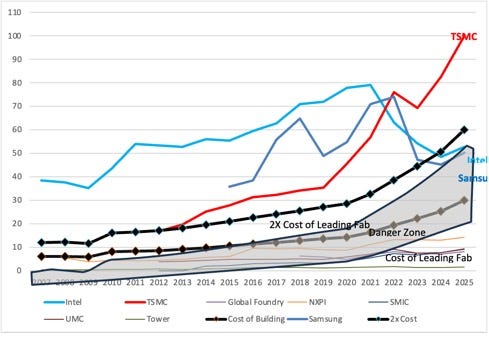

A useful rule of thumb holds that companies need revenue that is twice the cost of building an advanced fab in order to stay in the Moore’s Law race. Historically, companies that drop below that threshold eventually abandon the pursuit of leading edge capabilities.

Today, both Intel and Samsung Semiconductors have entered that “danger zone” where revenue is just below the threshold of that historical pattern. To be clear, this is just a pattern, not a hard rule. So the question is can Samsung and Intel afford to stay on the Moore’s Law treadmill?

Entering Moore’s Law Danger Zone

Source: D2D Advisory

The Leading Edge Players

TSMC

TSMC has emerged as the leader in manufacturing. In the chart above, as recently as ten years ago, there were many who questioned TSMC’s ability to remain in the race, but they emerged from the global financial crisis with some initial success with EUV systems. They built on that lead without stopping to this day.

However, we think it is important to note that TSMC’s history shows its success is not one of pure entrepreneurship overcoming all challenges. In its early days, the government of Taiwan provided direct (capex for their first fab equipment) and indirect (land and tax breaks) to help get TSMC off the ground. Later, the government seems to have suppressed the New Taiwan dollar which has provided a huge benefit to TSMC. Current estimates hold that the NT$ is about 30% undervalued relative to the US dollar. This has effectively made TSMC’s most important asset – its human capital – 30% cheaper. As we noted above, an important aspect of fab operations are the tangible skills around process design and manufacturing improvement, all of which is built by that human capital. That benefit has compounded over the past 15 years, allowing TSMC to continually invest in training and retaining its workforce.

TSMC has built on this advantage to continually extend its lead in manufacturing process. It is currently one to two years ahead of its closest rivals technically, and shows no signs of slowing down. It has also expanded its reach beyond manufacturing to advanced packaging, the intricate process of connecting chips to other chips and to the further elements in an electronics system.

Another, often overlooked advantage TSMC has is its maintenance of more mature manufacturing processes. For each new process node, TSMC has typically built a new fab, while keeping its older fabs running. TSMC recently announced that it is shutting down two fabs that were almost 20 years old. Given that over 85% of the world’s annual production of semiconductor units come from those older fabs, this has proven a lucrative strategy. These older fabs are fully depreciated, so while prices for mature nodes are much lower, they can be a source of meaningful profits. We estimate that in 2024, TSMC’s older fabs generated 48% of TSMC’s revenues, but over 70% of its profits. By contrast, Intel’s strategy led it to entirely replace older nodes with newer ones, leaving it with no trailing edge capacity.

TSMC is not perfect. Beyond its core capabilities it has struggled in more niche areas. Its silicon photonics process, while promising on paper, looks to still be a few years away from full functionality, and its RF SOI products lag considerably. These are just two, minor examples.

That being said, where TSMC really shines has been its approach to working with customers. The company was built from the beginning as a foundry for building others’ products. That has permeated the company’s culture. From personal experience, we know that given identical processes, we would pay more to work with TSMC because the time to market (and overall hassle factor) will be much better than competitors’. This stands in sharp contrasts to the next two players who are building foundry businesses on the back of giant internal customers.

Samsung

Samsung is often overlooked in discussions of the Foundry business, but it aims to compete at the leading edge. Samsung’s semiconductor business grew up on the back of its memory business where it is one of three segment leaders. While the manufacture of memory chips shares many technical similarities with the manufacture of digital logic chips like Intel and TSMC build, the memory business itself is very different. To a degree, memory is fairly commoditized in that one memory product is largely interchangeable with another. As a result, the memory business is driven by economies of scale, and the segment has consolidated down to three vendors – Samsung, Micron and SK Hynix – with Changxin Memory from the PRC (maybe) possibly breaking in.

Over the years, Samsung added digital logic products to its core memory business, and then entered the foundry business as well. For a time it seemed that Samsung would become a tough competitor for TSMC. The company has immense engineering talent and was able to win business through customer relationships from other parts of the Samsung chaebol. However, in recent years its progress has slowed considerably. Like Intel, it seemed to struggle to make the transition to EUV processes. While it has been pushing through, the gap between its most advanced offering and TSMC’s has been widening for several years. Critically, this shortfall has begun to impinge on the Memory business, where the company’s AI-targeted HBM memory has failed to win support from Nvidia, a key decision maker in this category. The company has also repeatedly lost major customers like Qualcomm. The depth of Samsung’s challenge is not entirely clear. As with Intel, Samsung Foundry has struggled with prioritizing external customers over its internal customer. The company maintains that its manufacturing process is now on firmer footing, but our discussions with external customers highlight many technical concerns as well as customer service complaints.

The Samsung chaebol has ample financial and technical resources to see itself through its current doldrums. That being said, we wonder how committed Samsung is to being a foundry. They make a lot of money from memory, while foundry is probably break-even at best. If the demands of foundry impede the company’s memory business will the larger organization consider abandoning foundry? Samsung insists this is not the case, but we believe customers are watching the situation closely.

Intel

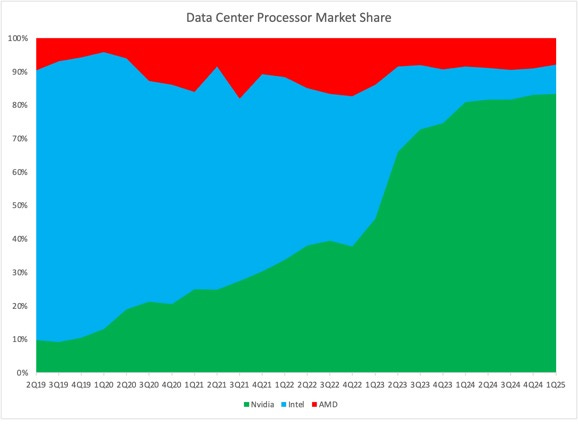

Intel was once the clear technical leader in semiconductor manufacturing. They developed a huge number of important technologies going back to the days when their co-founder literally coined the concept of Moore’s Law. But then they lost their way. Many case studies and business books will someday be written about Intel’s decline, and we imagine each will come up with its own critical turning point that marked the beginning of the end. For us, that moment occurred about ten years ago, when the company decided to delay moving to advanced lithography tools (i.e. EUV) as their engineers team wanted, and instead did a massive share buyback. From that point onwards, the company has struggled to stay at the leading edge of manufacturing. In particular, they seemed to have gotten stuck at the transition from 16nm to 10nm, a process they essentially just achieved last year. Over that time, they went from 90% share of data center spending to under 10%.

Data Center Processor Share

Source: Seaport and Company Data

Along the way Intel made a number of other critical missteps. They could not reach a deal with Apple who originally approached Intel to manufacture the A-Series chips to power the iPhone. Apple ended up going with TSMC, providing that company with massive volumes and the experience that goes along with it, and made TSMC the dominant provider of silicon to the smartphone industry. Intel also tried and failed repeatedly to become a foundry for third parties. Intel missed mobile, then missed foundry, while shedding trailing edge process capacity along the way. In all these cases, they failed to adapt their business model to accommodate external customers. The internal customer – their Products business – always took priority, leaving little room for outsiders. This problem became acute when Intel started slipping on Moore’s Law. Not only did they not have a foundry business to fall back on, but now their internal products were suddenly less competitive.

Eventually, Intel’s struggles became so glaring that its board took notice. They brought back long-time company veteran Pat Gelsigner as CEO who had an explicit mandate to lead the company’s charge to recapture manufacturing process leadership. He introduced his “Five Nodes in Four Years” initiative, a plan to rapidly advance the company’s manufacturing capabilities. Under this, Intel (finally) moved past the 10nm node where it had been stuck. The end goal of this program were the company’s 18A and 14A processes (very roughly equivalent to 1.8nm and 1.4nm respectively). The first, 18A, process would allow the company’s internal products to stabilize their competitive position against AMD, who relies on TSMC. By contrast, 14A offered a number of meaningful advances over what TSMC would theoretically be offering at the same time.

The company also formally separated into Intel Products (a designer of CPUs) and Intel Foundry (a Foundry). The hope was that 18A would attract initial interest from external customers. More realistically, it would help the company identify problem areas in its own customer service motions. And then with 14A start to gain more meaningful share.

Then things took a turn. The first warning signs were a number of public comments from potential Intel Foundry customers, most notably Broadcom, who strongly criticized Intel’s readiness for serving outsiders. Intel products were faring so poorly in the market, that they took the once-unimaginable step of signing up to become a customer for TSMC’s leading edge offerings. Earnings continued to decelerate, and in mid 2024 the company announced a 15% headcount reduction and (finally) ended their dividend. But that was not enough, and the for the fourth time in under ten years, the board replaced the CEO, installing long-time industry veteran, Lip Bu Tan.

Tan is the former CEO of Cadence Designs, a major supplier of software to the semiconductor industry. He is also a prominent venture investor. Across two firms and his personal investments, he has invested in well over a 100 start-ups, both in the US and in the PRC. That being said, while Tan is highly regarded in the industry and immensely well-connected, it is not clear that he can solve Intel’s problems.

On their last earnings call, Tan indicated that the company would abandon development of the 14A process if it could not find a large, external customer. He has also advanced the company’s ongoing negotiations with the US government in search of some form of support. As of this writing, the outcome of both of these fronts is unclear. Absent a major customer and/or government support, it now appears that Intel is preparing to abandon advanced semis manufacturing. A tragic outcome for the company that pioneered and led the field for so long

Intel’s Strategic Dilemma

Intel has arrived at the crossroads. The company needs to make some critical decisions. It needs to make them very soon. And the fate of the entire company is at stake.

Put simply, the company needs to decide if it wants to continue manufacturing semiconductors. If they choose to continue with the business they led for so long, then they need to invest heavily in advancing their 14A process, and they need to invest in the tools and systems that will allow external customers to use the process as well.

To accomplish this, the company needs some help. They are largely tapped out of their debt capacity (see above regarding that share buyback…). By our rough math, they need about $15 billion - $25 billion to accomplish this. This is on top of cash they generate from the Product side of the company and funding they have already received from the US government through the CHIPS Act. If they watch every penny and are highly disciplined in their spending, they might get by with less, but there will still be a significant, multi-billion dollar gap to fill.

For some reason, Intel’s Board has long seemed focused on getting that funding from the US government. Given recent headlines, it appears that negotiations are underway for such an arrangement. Of course, there is no certainty that this will happen, and even if it does, the details of such a deal will be incredibly important. Will Intel be required to advance to 14A and continue investing in advanced manufacturing? What will governance of the company look like?

For their part, it is unclear what the US government hopes to achieve. If the goal is to prop up a US company, get a stake in a big company at a theoretical discount, maybe generate some jobs through additional US fab construction – then they can get that in a way that does not mean much for Intel’s long-term future. If the government instead wants to ensure that a US company is capable of advanced semis manufacturing then they will need to write a large check.

Our preferred solution is for the government to instead negotiate investments by a host of potential Intel customers – Apple, Qualcomm, Nvidia, Broadcom, Google, Microsoft, etc. These companies all have a massive stake in Intel’s future. The trouble with this approach is that while all these companies have a long-term interest in securing an alternative to TSMC, short-term interest, quarterly expectations and inertia are all strong enough to make a deal unlikely. For some subset of these companies a collective $20 billion is both easy to raise and an incredible bargain. Ideally, the government would ‘encourage’ these parties to see past their short-term outlook and save Intel. Unfortunately, no one seems to even be considering this approach.

If Intel does decide to abandon manufacturing then it should act quickly. The Product side of the company has largely been built around its relationship with the company’s fabs. If those are going away, then the Product side needs to move quickly to TSMC in order to stay relevant As it stands now, there is still some level of internal pressure to work with Intel Foundry. The longer Product stays on Intel’s fabs, the further it risks falling behind competitors. Over the years, Intel has developed a reputation for its ponderous decision making, but it can not afford to straddle both side of this fence for much longer.

One final item to point out. Note that in all of the above discussion there is no mention of AI. In 2025, every semiconductor company in the world at some point discusses AI. Except for Intel. Intel does not have an AI strategy let alone an AI product. Unfortunately, there is nothing they can do about this until they sort out their manufacturing.

Derivative Impacts

A common argument now holds that there is no commercial justification for Intel to remain in manufacturing. TSMC has out-competed them, and no one seems worse off for it. This is the logic that has led the company to seek out government support. Absent a commercial justification for its existence, surely it has a national security justification.

While we certainly see the importance of Intel for the US strategically, we think there is a massive commercial need for its existence as well. As it stands now, TSMC has an effective monopoly on advanced semis manufacturing. “Effective” in the sense that both Intel and Samsung are still notional competitors. That, coupled with a strong customer-centric culture, have kept it from really flexing its competitive leverage. But that will change if Intel exits the business entirely and TSMC becomes an actual monopoly. Samsung will still be out there, but given that TSMC has been out-competing them for a decade and Samsung’s ambivalence about external customers, we think they will not be able to effectively curb TSMC’s advantages.

For several years, TSMC’s shareholders have been pressing the company to raise prices. They question why Nvidia – who is entirely dependent on TSMC – has much higher gross margins than TSMC. Absent a true competitor, we think it is only a matter of time before TSMC would raise prices.

The press is already reporting that wafer prices for TSMC’s upcoming 2nm process could reach as high as $45,000-$50,000/wafer, considerably ahead of the current $25,000 - $30,000 price. A TSMC price of $50,000 would fundamentally re-order the semiconductor industry. At those prices, only a handful of companies could afford ordering leading-edge products. Even large companies like Apple and Qualcomm would face significant gross margin pressure on their own products. We estimate that at $47,500/wafer Qualcomm’s gross margins would go to zero. These companies will still order chips from TSMC, but they will stay on older nodes much longer. Consumers would notice that new devices offer few improvements over previous generations. Only companies with the richest gross margins could afford to stay at the leading edge, effectively shutting out their competitors, and wreaking havoc with semis start-ups. This would be the effective end of Moore’s Law.

This will also ripple through the equipment side of the industry. We are already seeing Intel’s move away from past capex levels hurt earnings at companies like ASML and (probably) Applied Materials. TSMC would not only be the monopoly supplier, but also the monopsonist customer for the wafer fabrication equipment (WFE) industry.

In fairness, this is the worst case scenario. We imagine the US government and Intel will probably reach some kind of deal. And Samsung could very well turn itself around. But there is still a significant probability that both Intel and Samsung exit the business leading to the gloomy scenario above, and it is important that the broader industry recognize how much it will affect all of us.

If you like this content you should listen to our podcast.

Wonderful writeup. Now that the Intel has secured US funding, would you consider it to be slightly less probable that they exit business?